Facilitation – Making it Easy

I’ve been thinking recently about the meaning of the word “facilitate.” A dictionary provides this definition: “to make easier or less difficult; help forward”

This is different than the word “teach” – defined as “to impart knowledge of or skill in; give instruction.” Showing, explaining, and giving information are useful and helpful when the person being taught is in a state of readiness. But when that person is confused, frustrated, or even afraid — then repeated efforts to teach often have the result of simply adding to the confusion.

I am often asked to compare Davis methods with the many traditional tutoring-based approaches for dyslexia. These systems are geared to teaching struggling students to read, but rarely do they make the process easy. In fact, most are built around the assumption that progress will be slow and difficult, with an expectation that lessons will need to be repeated and revisited. They use words like “repetitive,” “explicit”, “systematic” to describe their approach. Some may be highly scripted and require orderly progression through a specific sequence of lessons or levels before the program can be completed.

But a one-week Davis program is not teaching or tutoring — instead, it is a process of facilitation. There are goals to be reached, but the crux of the program is to give the learner the tools to be able to easily and comfortably reach those end goals.

How can something that seems so difficult and arduous be made easy? One way is to change the approach – to find a different path. The facilitator must be able to recognize and identify particular barriers that are standing in the way of progress, to empathetically shift to the learner’s viewpoint, to be flexible and creative while still keeping the end goals in mind.

Patrick Courtois, a Davis Specialist in France, shared a story about a young client he once worked with that I think provides a good illustration of successful facilitation. (I have translated his account from the original French):

I was working with a ten-year-old child, who I will call Hector (not his real name).

The course was just beginning, and after showing him the first essential tools for the rest of the program, I reached for a book with the intention of asking him to read a few lines. This is part of the normal pattern of the course. It’s still a course aimed at reading, so you have to do that at some time.

With the book only lying on the table, I saw Hector become pale, his eyes filled with a kind of terror, as if I told him the worst torture. Of course, there was no way to go further with this book, but I would have to anyway before the end of the five-day course, Hector could face the monster!

So I had to quickly change the approach so as not to lose and inflict another failure on top of his already numerous negative experiences.

So I decided to shake up the normal order of the program, to adapt, to do only the bare minimum with a single objective: to make him read without his knowing it, to take him by surprise and to give him proof of his abilities and potential.

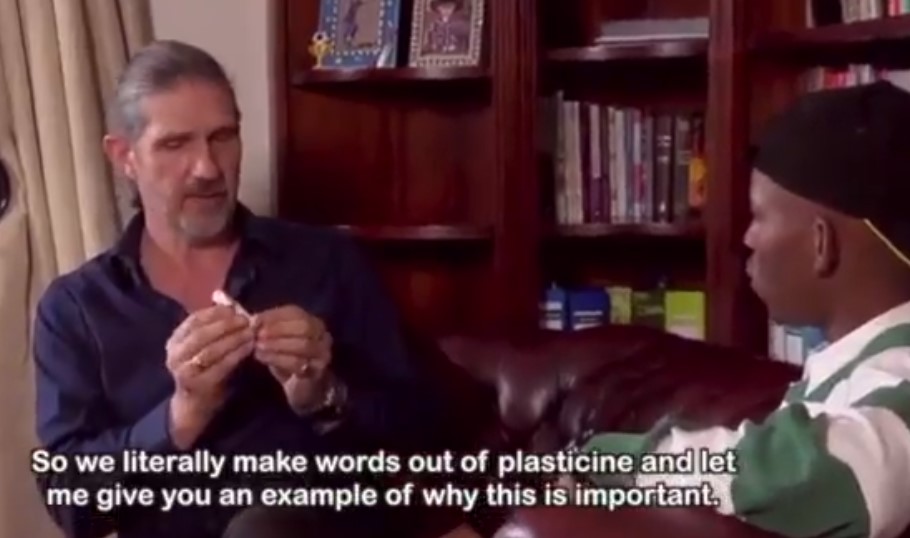

So we refocused the program on the words we created in modeling clay, one of the fundamental principles of Davis® program. I took the precaution, during the break, to print on a sheet of white paper a short sentence of about ten words, taken from a children’s book.

We then made each word in clay, but only I knew the real objective. From Hector’s point of view, these were only random words, but through our work with the clay, he would be able to easily recognize them.

After finishing these words, I showed him the printed sheet and asked him if he could recognize the first word. Then the next. And so on. As we had just created them, this exercise was very easy for Hector.

I then set my trap: “Hector, what you do you picture in your head?”

What he described to me was precisely the meaning of the sentence that he had in front of him.

So I continued: “Hector, do you know what you call what you just did?”

“No” he replied.

“It’s called ‘read’!”

Hector looked at me with incredulous big eyes. For the first time in his life, reading was not a nightmare, but a simple action to take, easy, obvious.

We spent three hours to read half a page, but it was the greatest reading he had ever done.

I asked him: “Hector, how many pages do you want to read tomorrow?” He answered “three”, then immediately retreated, “Uh no, one.” The next day, we read four pages.

The moral of this little story: I think one of the best ways to deal with anxiety as overpowering as Hector’s is to give the positive experience of the simplicity of reading. The final word from Ron Davis: “Dyslexia is a combination of simple elements to manage one after the other.” The whole is to assemble these simple elements and put them within reach of the learner.

On his website at www.infodyslexie.org, Courtois explains the results of a Davis program:

A child who used to say ” I am nothing / dumb / incompetent ” almost always changes his speech to ” I do not know this yet, but I can learn to master it “. This change is an opening to the future and a change of state of mind.

This article was first published in July 2019.