Too Hard, Too Soon

I walk into the classroom and sit down beside the child who’s on my caseload. She has OT services “push-in”, meaning that I don’t pull her out to my therapy room, but just go see her in her classroom and work alongside her there.

We’re only supposed to work on handwriting, but it’s really hard to do that, because she’s struggling so much in every way.

When I arrive, she’s seated in a group with other classmates working together. I consider leaving — it’s difficult to find just the right time to do “push-in” OT, the balance between letting kids have normal classroom time with their peers vs actually being able to help them. She waves me over, so I don’t leave. I sit down beside her. “Hey, what are you guys working on?”

One of the other girls in her group of friends points to her paper and says “We’re all already on question 4 and she’s on question 1. We won’t read it to her. She’s supposed to read it herself.”

She makes what I’m guessing is an uncomfortable smile, behind her mask, and puts her finger on the first word of question 1 again — “Which”. She can’t quite sound it out, but she tries again: “Wuh-huh-ih-cuh-huh…”

“-ch makes a ‘ch’ sound,” I suggest, trying not to just give away the answer immediately.

She nods and tries to read it correctly. But by the time she’s gotten to the -ch, she can’t remember the prompt I just gave, so she reads it out sound by sound exactly the same way.

Her peer rolls her eyes. “She’s in second grade, she should be able to do this by now.”

For the rest of the time I spend with her, I make it a point to read her whatever she can’t read, without judgment. A couple of times, I even start reading the sentence at the same time she does — because to her credit, she just never stops trying — and then I see a little burst of validation in her eyes when we simultaneously read simple words like “The dog has…”

I don’t blame the other seven-year-old in her class for thinking that she’s just not trying hard enough to read correctly. It’s a fault in the whole entire system. She’s being dragged along by a curriculum that she’s nowhere near able to keep up with, and doing work that’s developmentally inappropriate, and I’m supposed to sit alongside her while she does that work and make sure her letters are formed right — while her mind is frantically trying to remember 30 different things that she “always does wrong” on top of a battle against whatever internal discouragement might be there.

She’s seven. Seven is the age when children’s hands mature into the ability to grasp better, when their minds make a shift to be ready for different kinds of thinking. Maybe in another world, where we had let her wait until now to start memorizing the letters and their sounds and their shapes, maybe she would have gotten it right away. But “she should be able to do this by now”, the world around her says, so she’s already supposed to be writing complex sentences conjoined with complex punctuation, she’s supposed to read words like “encouragement” and “contraction”, and meanwhile she’s still struggling with any words harder than consonant-short vowel-consonant.

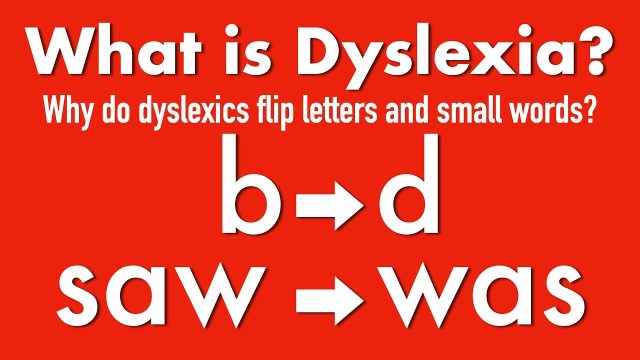

And there’s nothing I can do except sit beside her and try to help her tease out the difference between b and d, between f and r, and remember which letters go up and which ones go down below the line, and hope it’s enough, and walk away knowing it’s not enough.

The story didn’t end here. I wrote this reflection a year ago, at which time some people were — rightfully — really upset with me for “not doing more”. I was writing about a snippet of time, not a child’s entire course of treatment. A year later, some things have changed. New supports are in place. I continue to advocate for this child, and so do the other adults in her life, in every way we can.

The system is still broken. She still internalizes her fault in this brokenness, in “just not getting it”. We work on it. She excels incredibly at some things. She lights up when she gets to pursue them. I try to find that light and expand it, instead of just mucking around in the things she can’t do.

It’s hard work. It’s long-term work. That’s what we do here.

I am nearly 80, and my dyslexia was self-diagnosed. I have written over 300 essays, stories, and snippets, yet have published nothing. I have written a book, also not published, about my military experiences from 50 years ago. Since awareness, I have known I am different, and I thought – dumb. After failing my way through high school, I was given an I.Q. test and a score of 126, which no one explained, so I still thought I was dumb. In mid-life, I again had my I.Q. tested and tested a second time. They said the first test was no good, as I was not supposed to be able to answer all the questions. The second test showed an I.Q. of 131, yet again, it was not explained to me, so it was another ten years before I discovered I was intelligent. Yet, as I have learned, there is a difference between being smart and being intelligent. Intelligence has to do with what you can do, and smartness has to do with how you use it.