Teaching Japanese to dyslexic students

Reading and writing difficulties associated with dyslexia can extend beyond the native language of a person. The explicit difference of letters (graphemes) and sounds (phonemes) in a language make the learning process more complicated. Dyslexia is more evident in languages where the same phoneme (a sound) could be written with different graphemes (letters) as in French or vice versa.

With this in mind, dyslexia was once thought to be very rare in languages with hieroglyphic writing, such as Chinese or Japanese. However, this is not true, because dyslexia has a neurological nature and people of all language backgrounds can have its symptoms. While in Western countries the dyslexia phenomenon has been closely explored, in the Japanese education community problems of dyslexics has been silenced for a long time, and only with the book “読めなくても、書けなくても、勉強したい” (I can’t read or write but I want to learn) by Satoru Inoue, the matter started to receive public attention.

Because the hieroglyphs appear more as picture-like signs, they seem to be easier to understand for dyslexic people. Dyslexics are often referred to “picture-thinkers”, because they would more likely associate images with the visual characteristics of an object, rather than its name. However, the Japanese written language has a more complex structure than many people believe. In Japanese we have three types of writing, i.e. two syllabic alphabets of Kana, and Kanji hieroglyphs.

The Kana has quite simple sound-letter correspondence, however, its writing still could be confusing; consider:

さ for “sa”-sound and ち for “chi”-sound in hiragana and ツ(tsu) シ (shi)ノ (no) and ソ(so) in katakana.

When it comes to kanji writing, the situation might get even more complicated. Because of the Chinese origin, some kanji have both Chinese and Japanese ways of reading. In addition, even if you can guess (to some extent) the meaning of a kanji, you will not be able to read it correctly without knowing the reading.

Additionally, dyslexic children can invert words or replace letters or sounds of similar appearance, thus “was” will be read as “saw” and “d” becomes “b”, as well as Japanese “お” turns into “あ and “さ” is reversed to “ち”. Because of inability to memorize and repeat the direction of lines as well as failure to notice tiny differences of a character, dyslexics can also experience difficulties in recognizing kanji as well: 特 (time) and 持つ (to hold). Also, problems of distinguishing the elements and stroke direction could appear in writing of kanji combinations:

犬山→太山, 三郎→ 三限.

Tips for teaching Japanese to dyslexic kids

In my teaching practice I have worked with children having problems in recognizing and writing letters and numbers. Another common problem was a difficulty in memorizing the text kids had just read. Since the best way to help dyslexic children memorize material is teaching them with a multisensory approach, I tried to layer as many perceptual styles as possible in my lessons.

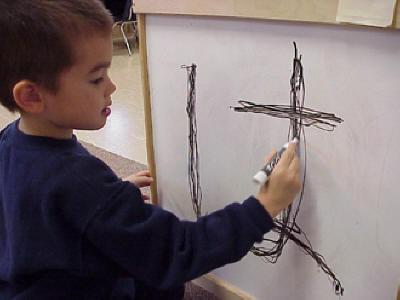

As Japanese characters look much more like pictures, children enjoyed drawing and painting them. Let children use any technique they may like – pencil, paintbrush or their fingers; your aim is to keep them interested in the activity. It is necessary to control that a kid draws kanji in the correct manner, i.e. paying attention to the strokes number, their order etc. You may do this drawing exercise in a form of game and ask the child to repeat kanji after you (or, as a home assignment, after animated picture of a kanji).

A good way to help a child read and understand a text could be a listening to the voice record of the text. While listening to the record, a child should follow the lines in the textbook – in this way written characters would obtain a sound image. Note: make sure the child does read what is written, not just recalls what he or she has heard! For this, you can slightly change the text (keep the vocabulary same, but make other sentences).

Teach your students to use folders for keeping materials of different lessons. You may use different bookmarks or highlight topics with bright colors – it will help dyslexics quickly navigate through the folder and find required information. Moreover, keeping things nicely organized will help dyslexics be more focused and disciplined themselves.

Do not forget about innovations! Personal computers and gadgets could be a great help for people with language-related difficulty, being an educational and working tool. For example, dyslexics can use a tablet as a tool for writing essays – the auto-correct will highlight the mistakes and attract writer’s attention to the misspelled word. However, do not let children rely on the software completely – a computer should help, not replace child’s own skills.

The extensive use of flash cards, game exercises and technical tools in educational process helps to increase the productivity of learning process and to form a positive motivation of children. Keep in mind that children with language-related difficulties tend to get tired more quickly and could be easily distracted, thus it is important to switch their attention from one activity to another. Also, a teacher should not overload them with new information, gradually moving from simple to more complicated tasks; it is better to keep the process slow, but productive.

My 8 year old son is bilingual English and Japanese and goes to a Japanese school. He has systematic difficulty with mirror image directional differences, for example 人 and 入, in English b and d, and numbers 6 and 9. Writing in multiple languages takes things to another level of complication for dyslexics because confusion can happen inter linguistically as well as intra linguistically: for example because some kana are similar to letters he often writes the コ in his own name backwards, confusing it with c. We found interactive kana and kanji learning games for iPhone and iPad to be very helpful for keeping his attention (he’s also got ADHD), and for helping with memorisation. Overall he seems to find kanji easier to learn because they represent images.

Nice article!

I just noticed a small mistake with the example for confusing 特 and 持つ;特 means special (the kanji for time is 時). Maybe a more striking confusion would be between 待つ (to wait) and 持つ (to hold), especially knowing that the 2 words have a similar pronunciation.