Finding Fluency

All I wanted was for my son to become a reader. I wanted him to be able to read easily and automatically, without effort. I wanted him to be able to look at words on a page and recognize them instantly, without conscious thought. I wanted him to be able to read for pleasure.

In other words, I simply wanted my son to be able to read fluently – just as I did, just as his father did, just as even his younger sister could, despite their 5-year age gap. But for my son that goal was elusive. He was smart, he understood the mechanics and the rules that he was given. The motivation was there – he was willing to try new things, but again and again he would tell me: “I already know that stuff. It doesn’t help.”

Fluent readers do not need to think about the mechanics of reading, but can instantly and without thought recognize most of the words they encounter in connected text. Reading seems natural, and their mental energy is focused instead on finding meaning — on following the plot of a story, or learning new facts or insights about a subject.1 Educators often include reading expression or prosody as part of the definition – and that is valuable – but that is a quality tied to oral reading. Outside of a classroom setting, most reading is done silently, Skilled, fluent readers typically read silently somewhat faster than they speak or can follow spoken conversation.2

Fluency is not simply a matter of speed; even the most fluent readers will vary their reading speed depending on the context of the reading and the level of difficulty of the material. To gain fluency a person must have built up a large internal reservoir of stored words or word segments that are instantly recognizable. And the person needs to be able to move through the text at a rate that matches their ability to comprehend the information contained in the words. It needs to be fast enough so that the reader experiences a sense of the flow of language, but not so fast that they lose track of meaning.3

I think it’s something like learning to ride a bicycle. Too slow, and the bike simply is going to fall over. At first, a new rider will have difficulty — their bike will wobble and they may fall. But along the way something clicks and the rider gains the ability to balance and peddle and steer all at the same time. As the rider gets more practice, the skill soon becomes second-nature. Reading fluency, like bike-riding, is tied to procedural memory – the “how-to” part of our brain that is internally generated and enhanced with practice, rather than the facts and information storing parts of our brain. Yes, there is overlap — but a skilled reader would not have to think about a rule about silent e’s in order to read the words bike, practice, nature, and rule which were used in this paragraph.

For typically developing readers, the transition to fluency seems natural. A small child will start out reading in a hesitant and halting manner, pausing to decipher each word in turn. This might be tied to the process of the brain’s rewiring itself to foster reading, to merge the knowledge of meaning and pronunciation with the visual perception of the unique strings of letters evoking each word. In any event, there comes a time when the child has acquired a sufficient internal automized word bank, and the process of reading flows. Once this happens, most children can transition to a phase of “self-teaching”, where they are able to acquire an ever-growing store of instantly recognizable words through independent reading. 4

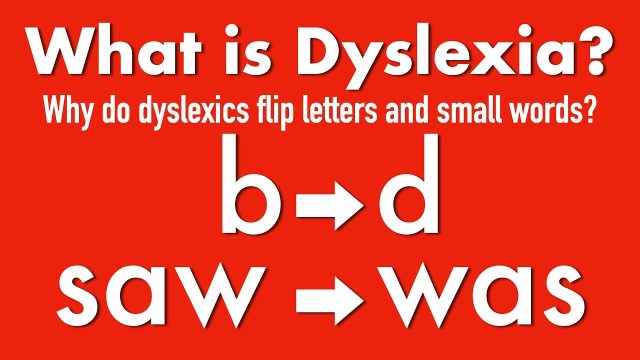

But this doesn’t happen so easily for dyslexic readers. A persistent difficulty with acquiring reading fluency is a hallmark sign of dyslexia, and one of the most enduring qualities. Like my son, the dyslexic reader will seem stuck at that beginner, early-reader phase. Underlying skills may improve, but the process of reading remains slow, halting, and laborious.

Nonetheless, many dyslexic individuals do become capable and fluent readers. Somewhere along their personal trajectory of reading development, they get to the place where their brains are able to integrate all the different bits of information that go into reading, and pages of printed words begin to make sense.

This happened for my son at age 11, when I guided him through the orientation process as described in The Gift of Dyslexia. I didn’t understand how or why that could possibly help, as the process did not seem to be tied to any particular reading skill. But we were both eager to test his new-found orientation point.

I handed my son a book, opened it up to a random page, and asked him to read aloud. I was amazed. He was amazed. There was no sign of the slow and halting, error-ridden delivery that had been his norm. Instead, he read smoothly, confidently. The book was at an appropriate level for his age, but well above what had previously seemed to be his attained level. He still hesitated from time to time, but now the hesitations were brief, As I noted down the words that gave him pause, I could see they were all small words on the Davis trigger word list. Mostly pronouns and prepositions. So we had a breakthrough and a way forward.

From then on my son’s own motivation took hold. He became an avid reader, reading constantly, one book after another. At first, he chose to practice with easier books, but in a few months, my son was reading well above grade level. He went on to excel in high school and beyond.

Unfortunately, scientists and educators have not focused much attention on exploring how dyslexic readers transition to reading fluency. One researcher who did seek out those answers is Rosalie Fink, who studied literate and highly-accomplished adult professionals with a history of childhood dyslexia. She found that some had completely overcome early problems tied to reading; others read well but had ongoing difficulties with spelling, and others had strong reading comprehension skills but still had some difficulties with word recognition and oral reading. Most of her research subjects had become readers between ages 10 and 11, usually driven by passionate interests that fueled them to read avidly once acquiring the basic skills. She wrote, “development of basic fluency, of … ‘getting it’ was an ‘Ahaa!’ experience for many, recalled with vivid emotions and clear memories.” 5

My son’s experience with Davis Orientation gave him a different way to focus his mind while reading, one that allowed his brain to integrate and harmonize all that “stuff” he said he already “knew.” And once he had fluency, he also had the power to improve his reading skills through practice, as well as heightened motivation once the task of reading had become pleasurable rather than onerous.

However, many dyslexic children never find the key to reading fluency, not because they are incapable, but because long-held assumptions about teaching reading often work against them. The standard educational response is to provide extra instruction geared to specific skills where the child is weakest; usually, this involves intensified instruction in phonetic decoding strategies. Although well-intended, this approach is often counter-productive. The child is given more information than they can manage in an area of weakness, when they need a way to integrate an array of skills tied to reading.6 It is well-known that dyslexics who become readers rely primarily on areas of strengths (generally described as “compensatory” strategies) – but rare for children to receive early encouragement to develop or apply those abilities.

I don’t think that reading fluency should be left to chance. While some dyslexic children, like Dr. Fink’s adult research subjects, might eventually gain fluency through their own persistence, it is not something that merely comes with time or age. Many of Dr. Fink’s subjects were highly educated and had received years of specialized tutoring as children, but made comments like this: “To this day, I can hardly sound out a word..” (from a speech pathologist). “Phonics doesn’t always work.” (neurologist). “I can’t sound out anything.’ (gynecologist) “I had phonics training in the resource room, but it never got into my head.” (biologist).

Fluency requires a merger of skills, in the context of reading meaningful text — so children should be provided with all the tools needed to reach that goal from the outset. Kids can become capable and confident readers through strategies geared to their natural strengths.7 There is nothing wrong with also offering help with basic skills, but it is a problem when the goal of fixing a specific weakness supplants the more important goal of enabling the child to become an independent reader.

This article was first published in August 2020′ this article has been updated with additional research links.

References

- Reading fluency is defined as “”the ability to read connected text rapidly, smoothly, effortlessly, and automatically with little conscious attention to the mechanics of reading, such as decoding.” Meyer, M. S., & Felton, R. H. (1999). Repeated Reading to Enhance Fluency: Old Approaches and New Direction. Annuals of Dyslexia, 49, 283-306

- For more discussion of the differences between oral and silent reading fluency, see Share D. L. (2008). On the Anglocentricities of current reading research and practice: the perils of overreliance on an “outlier” orthography. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 584–615.. (“Reading aloud … does not necessarily involve access to meaning—the goal of word reading.” “[D]yslexics are well known for their relative dissociation between (silent) orthographic strengths and (oral) phonological weaknesses.”)

- “Fluent readers process written text rapidly and accurately, and comprehend what they read.” Benjamin, C. F., & Gaab, N. (2012). What’s the story? The tale of reading fluency told at speed. Human brain mapping, 33(11), 2572–2585.

- Share, D.L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55, 151-218.

- Fink, R.P. Literacy development in successful men and women with dyslexia. Ann. of Dyslexia 48, 311–346 (1998)

- For example, brain regions tied to executive control have been shown be implicated in reading fluency and comprehension. Roe, M. A., Martinez, J. E., Mumford, J. A., Taylor, W. P., Cirino, P. T., Fletcher, J. M., Juranek, J., & Church, J. A. (2018). Control Engagement During Sentence and Inhibition fMRI Tasks in Children With Reading Difficulties. Cerebral cortex, 28(10), 3697–3710

- For an example of significant improvement in reading ability following short exposure to a compensatory strategy, see Werth, Reinhard. Rapid Improvement of Reading Performance in Children with Dyslexia by Altering the Reading Strategy: A Novel Approach to Diagnoses and Therapy of Reading Deficiencies. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience,vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 679-691