When the “Evidence” doesn’t fit

What truly constitutes an evidence-based approach for a neurodivergent population?

An evidence-based approach is important so that those looking into methods can be assured that the method they are considering doesn’t just help a very small minority of people within the population group. But it is also very important when looking to evidence-based methods that we understand the limits of what is considered to fall within that mantle by many people. It is commonly considered that unless there have been large-scale, reproduced studies, a method cannot be accepted as evidence-based; no matter how effective it appears to be based on other supporting research.

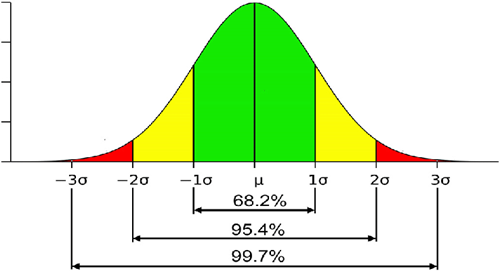

The normal curve of distribution applies for any population. Large-scale studies are

generally on a wider population, rather than only those falling outside the “green zone”

shown in this diagram.

This means that by definition, there will be a significant percentage of the population who are not helped by even the most widely studied methods and approaches.

As noted in another article on this blog, the phrase “evidence-based” is often tied to phonics-based tutoring programs, even though evidence shows these programs to be ineffective for large numbers of dyslexic children. Researchers may label the 20 to 40% of dyslexic children who do not improve with these interventions as “treatment resisters” or “nonresponders”. 1 2

This is not at all surprising, given that there will be a normal distribution curve within the dyslexic population, in addition to them already falling outside the norm in the wider population.

If the term ‘evidence-based’ is to be useful for the neurodivergent kids and adults who fall outside the “green zone” (32% of the population), we must take that into account when looking at the evidence base. To truly be of service to those in the population who fall into the yellow and red zones, we need to look beyond the large-scale, reproducible studies; for example to approaches where the creator of the approach is outside those statistical norms themselves, and truly understands what the population needs.

This can be seen in the case of the Davis Dyslexia Correction approach, by way of example. More than twenty years of independent research has shown the program to be effective, but most are case studies or smaller group studies, given the individualized nature of the program. 3

It will take a very long time to develop a large evidence base for a method that serves the “yellow and red” section of the population, as funding is generally only available for large-scale reproducible studies on much bigger populations. So it is essential that we embrace the smaller studies that are targeted to this more narrow population.

Those who fall within the yellow and red zones of the normal distribution curve are really being failed when it is not taken into account what truly represents an evidence base for them. It is extremely disappointing to see that in many cases instead, the term ‘evidence based’ is being used to dismiss methods and approaches that could really help these already marginalised populations. At the same time, this standard is not applied to widely-accepted traditional approaches, even though neutral agencies have repeatedly concluded that there is little to no evidence to support them. 4

References

- Torgesen, J. K. (2000). Individual differences in response to early interventions in reading: The lingering problem of treatment resisters. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 15(1), 55–64.

- Al Otaiba, S., & Fuchs, D. (2002). Characteristics of children who are unresponsive to early literacy intervention: A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 23(5), 300–316.

- See Davis Research Studies and Davis Methods Compared.

- See Research Topic: Orton-Gillingham based teaching