The nonsense of teaching nonsense words

Dyslexic children often experience difficulty with phonetic decoding. Researchers and educators use nonsense words – also called nonwords or psuedowords – as a tool to assess phonetic decoding ability. These nonsense words are letter sequences that follow regular phonetic rules and are pronounceable, but have no meaning — for example, bif or yom or mig.

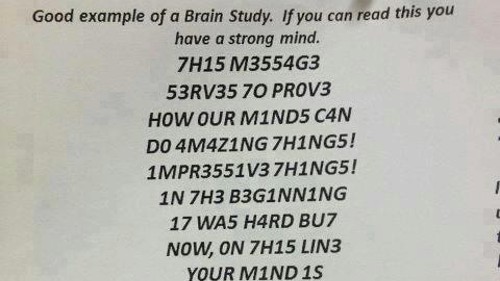

Many schools also have implemented tools to measure early reading ability such as the DIBELS assessment, which include tests of the ability to decode nonsense words. It makes sense to include nonsense words for assessment purposes. At least in theory, that can help sort out whether a child’s reading difficulties stem from difficulty with phonetic decoding or from some other cause, such as visual or surface dyslexia.

Because this is a skill that children are now tested in, it has now also become a skill that is increasingly being directly taught. Part of this is a teach-to-the-test mentality — if “Nonsense Word Fluency” is part of the assessment regime, then the most direct way for a teacher to assure that her students can pass the test is to invest time in teaching the underlying skill. And because dyslexic students have persistent difficulty with phonetic decoding, then it might seem logical to invest extra effort in helping struggling readers gain this ability. Many websites provide free instructional worksheets for teachers to use, including materials labeled as “DIBELS practice” and recommending “repetitive practice.” Many of these materials contain words drawn directly from the DIBELS assessment.

Unfortunately, this teaching practice undermines and invalidates the use of the assessment. According to literacy expert Timothy Shanahan, “This teaching is a waste of time for producing readers and renders useless the intended improvement in test design.”1

The whole point of testing a child’s ability to decode nonsense words is to assess their ability to rapidly decode unfamiliar letter sequences. But if children have been previously exposed to the same letter patterns via worksheets or practice sessions, then there is no way to sort out whether the child’s performance on the test is due to phonetic ability or memorization.

How this strategy hurts dyslexic kids

Rather than helping, this teaching strategy makes it more difficult for dyslexic kids to learn to read.

To start with, valuable class time is wasted teaching children to decipher words that don’t exist.

Many of the letter patterns are sequences that are unlikely to be encountered by the child in real reading environment. For example, the nonword qif found on the sample worksheet above is not only a nonsense word, but it is also impossible to decipher using common English conventions. In English, q is always followed by the letter u, and the consonant-vowel sequence qi is encountered only in a handful words derived from foreign languages that young children are unlikely to encounter in print. And how would qif properly be pronounced? The correct pronunciation might be “chif” (as in qi, a Chinese word meaning life-force) , or “kif” (as in qintar, an Albanian monetary unit) — but will the teacher offering this worksheet know that?

Even more frustrating — perhaps even cruel — is the practice of using worksheets with mixed real and nonsense words, requiring the child to identify which is real. Given all the other problems the dyslexic child experiences, including letter confusion and the tendency to reverse, invert, or transpose letters, together with possible difficulty distinguishing certain vowel or consonant sounds, it becomes an impossible task.

Certainly it is likely to create more confusion. For example, the “Fish Bubbles” worksheet shown here contains the word kod, directly opposite a picture of a fish. If the goal of the exercise is to teach phonetic decoding, then it would be logical for a child to read that letter sequence as the phonetically identical real word, cod. The same page has the nonword ros – which a beginner might mistakenly sound out as rose. Dyslexic kids commonly confuse the letters b and d – five of the words on the page contain one or both of those letters.

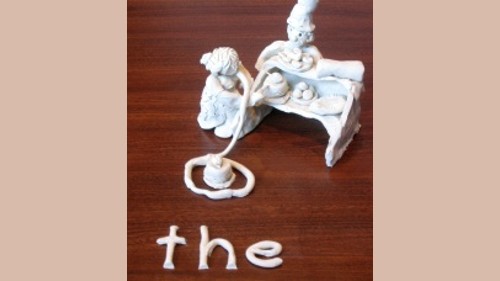

An additional problem with the nonsense word approach is that English is simply not phonetically regular or consistent. No matter how well a person learns to decode, the language is full of rule breakers, starting with common sight words that small children routinely must learn, such as one, the, two, you, who.

So in English – in order to be certain of how a word is pronounced, we need to know more than the letters in the word; we need to know what the word means. Or, as Dr. Shanahan wrote, tests of nonsense words “prevent students from any kind of self-evaluation and adjustment of pronunciation, key aspects of decoding.”

And for dyslexic learners, meaning is particularly important. Study after study has shown that dyslexics who become good readers do so by relying on meaning-based strategies. After all, if the part of your brain that connects letters to sounds does not work efficiently, that is all the more reason to utilize more efficient mental pathways to puzzle out new words.

So when a beginning reader can recognize a known word, there is an immediate mental reinforcement. The child sees the letters, d,o,g; the child attempts to put the sounds together – du, oh, guh – and then the riddle is solved when the child is able to connect the sounds to the known word, dog!

But with a nonsense word, the child is deprived of that self-reinforcing step of word recognition and confirmation. With every mistake, the dyslexic child ends up feeling frustrated and demoralized. The experience makes it even more difficult for the child to learn to phonetically decode real words, because the child has been led to doubt his own abilities. Instead of understanding phonics as a system of clues that can lead to recognition of familiar words in print, the child may be internalizing the message that phonetic decoding is something mysterious that he cannot do.

The use of nonwords in teaching is completely unnecessary. Despite the many rulebreakers in English, the language is also full of phonetically regular words that can be used to teach letter sounds in a fun and pleasurable way: cat, mat, hat, sat, bat. Dog, log, bog. Hit, bit, kit. All of these are real words that the child can recognize and understand, and which can be used to form meaningful sentences that the child can read. Because of the frequency of these very common onset-rime patterns, learning them can also open the door to reading real sentences in real stories geared to children. Teaching phonics in the context of real words also provides the opportunity to explore how vowel sounds change in combination with additional letters and syllables — how bus becomes busy, bit becomes bite, man becomes many.

If any particular sound exists in real words and can be represented by a letter sequence, then those words or real syllables can be used to teach the phonetic pattern. New letter sequences can be introduced along with new vocabulary, with each pattern reinforced through exposure to multiple examples. And of course, if that sound and letter sequence doesn’t exist — then there really was no point in teaching it.

- Shanahan on Literacy, “Which Should We Use, Nonsense Word Tests or Word ID Tests?” Posted 26 August 2023. ↩︎

This article was originally published on March 18, 2018; it has been most recently updated in September, 2023.

Thank you for this, I agree with you, it is bad enough that spelling words are a slow process, that having been exposed to nonsense words only make remembering the correct spelling harder. I am going to take a civil service exam next month and some of the practice questions are to find spelling and grammar errors in a passage,…I practice but my grade is always 50/50. 25 right out of 50. I believe dyslexics remember spelling by repeating, when I worked over 25 years ago in a insurance company we did monthly “reconciliations” I could write that word by “hand mussels memory” I had to use spell check just now to write the word:(

You make a good point. One needs to be careful in the choice of pseudo words. You are correct that qib would be a poor choice. That said, we have had tremendous success teaching dyslexics to read using pseudo words. Once pseudo words are mastered, fluency in similar real words is much easier.

Dog may well be “read” by memory requiring no decoding skills. On the other hand sog & rog must be decoded. Another reason for using pseudo words is that longer words multisyllable are made up of pseudo word segments. Hence entertainment is en (cv,) ter (cvc), tain (cvvc), ment (cvcc)

Actually, “en” and “sog” are real words, not pseudowords. A child learning those words using Davis strategies would know that, because looking up the dictionary definition would be part of the process of learning.

Longer, compound words are generally made up of common morphological elements. The root “enter” can be found at the beginning of 207 English words. The suffix “tain” can be found in 247 words, and the suffix “ment” can be found in more than 1700 words. So following a meaning-based approach that uses real words can be far more powerful — and certainly does not in any way stand in the way of learning the phonic elements. That is, if the child’s first exposure to the “en” combination is in the word “end” – that child has learned the common VC combination. A spelling list with words such as end, ten, men, pen, hen, den – would reinforce that understanding, all with real words.

Psychologists (I’m one of them) use pseudo-words only to assess whether the student is applying phonics skills accurately. If anyone tries to teach specific nonsense words, it defeats the entire, necessary advantage of the test data that psychologists can interpret among other measures (letter and word identification, oral reading fluency, silent reading fluency, oral vocabulary, reading vocabulary, and reading comprehension, working memory, processing speed, rapid naming, verbal comprehension, etc. for example). I am fully on board with discouraging teaching phonics using nonsense words. Teach phonics with real words. In a teaching context, it is easy for a knowledgeable teacher to determine if the student is reading the word by sight (the desired endpoint) AND if the correct orthographic mapping is in place (can the student identify what sounds are needed to construct the word, what order those sounds need to be used in, can they blend the sounds together, can they recognize that ‘o’ can make multiple possible sounds and can they chose the correct sound if they were to demonstrate sounding out the word (to a younger child? for example)). You don’t need nonsense words in a teaching context to teach knowledge and application of phonics.

I re-iterated the author’s main points on those topics to make it clear that I am in overall agreement. However, I think it’s important to recognize that the science isn’t described correctly if you say “Study after study has shown that dyslexics who become good readers do so by relying on meaning-based strategies. After all, if the part of your brain that connects letters to sounds does not work efficiently, that is all the more reason to utilize more efficient mental pathways to puzzle out new words.”

I am fully in agreement that making meaning and meta-cognition (thinking about thinking/reading) are very important for students with dyslexia. However, studies also show that the only road to efficient reading is by creating pathways that are more like other efficient readers, i.e. orthographic mapping – mapping letters to sounds. The reading pathway that works efficiently is letters to sounds to meaning. Effective intervention makes dyslexic brains (the processing that occurs in them) look more like typical brains (not quantitatively more of their original pathways.

So “. . . if the part of your brain that connects letters to sounds does not work efficiently, that is” (NOT) “all the more reason to utilize more efficient mental pathways to puzzle out new words.” Rather, it is all the more reason to focus on practice and repetition and strengthening the connection between letters and sounds to make it more efficient”.

Again, I agree with the point that teaching nonsense words is nonsense, but not that people with dyslexia need to utilize more efficient mental pathways. They need to make the pathways that are efficient for reading more efficient.

Sara, you might want to familiarize yourself with the research summarized in these articles:

* Research Update: Morphemes, Meaning, and Dyslexia

*New Research Confirms that Dyslexics Read Better with Right Brain Strategies

There’s now a body of research going back more than 20 years which has consistent results. When brain scans have been done comparing dyslexics who have overcome reading difficulties (“compensated”) with so-called “normal” readers and/or with dyslexics who continue to struggle, the research shows that the capable dyslexic readers have developed alternate pathways.

I am a counselor at an elementary school and it literally enrages me that they are teaching this when practical spelling lessons have gone out the window. Second graders cand spell basic word yet we give them nonsense words that are not even phonetically accurate. I was in a special ed room the other day and they were doing a nonsense word activity. They had to turn blerp in to what sounded to me like bloop, like a fish, and they spelled it blup. Well for someone who knows how to read those sounds are BL and UP. NOT BLOOP! I am mortified. Bring back spelling/vocab books!!!!

I totally agree!! My school continues to write goals that sat student will read 45…nonsense words. Any research you can share, I’ve only found one.

Having a goal to teach a specific number of pseudowords would definitely not benefit struggling students. That being said, there is a period in word reading development when incorporating some pseudowords during instruction makes perfect sense, and this is because many children in the early phases of word reading development can learn to depend on visual memory of many words without having to ever understand the alphabetic principle or use the letters in words at all to “read” the words. Thus, they bypass learning how to decode. This in turn becomes a problem because memorization of words will only get them so far. At some point, words will become more complex, and they will not have the proper tools to decode unfamiliar words. If you ask a non-decoder to read the words cat, sat, and hat, they may do it perfectly, giving the false impression that they are decoding when really, they’ve just seen those words enough to remember them upon sight. If you want to make sure that they are learning and using decoding skills to read words, then incorporating a pseudoword or two into instruction here and there will (a) force them to use all the letters in the words, thereby ensuring they are practicing decoding and not rote memorization, (b) give them additional practice with more possible letter combinations and variations that are often found in common spelling patterns and that they in fact may encounter later in longer, multisyllabic words, and (c) make planning letter/sound manipulation activities easier for you as you can build and deconstruction more practice items during word work with manipulative letters. In other words, you can go from real words to non-words and back again, providing more combinations and more opportunities to practice (e.g., Read this word: mat. Now, take away the letter m and replace it with the letter s. What does it say? Sat. Now, take away the letter t and replace it with the letter n; What does that say? San. Now, What would you need to add to the end of this to make the word sand? The letter d! Now, I’m going to take away the letter n. What word is this? Sad). This is a common activity to help children decode and the addition of the psuedoword, san (which by the way does have an official meaning, but not to most children learning to read), only provides an additional opportunity to practice using their knowledge of how letters and sounds work and provides exposure to letter combinations they are likely to see in other longer words. I’m not saying that your goal should be to teach large numbers of nonsense words, or that you should focus on teaching specific lists of these words so that children will perform well on the word attack subtest of the WRMT or the TOWRE, but I assure you that incorporating some pseudowords into this type of instruction will not harm anyone.

English is morpho-phonemic — that is, morphology dominates over phonology in spelling. That’s why the word “read” can be pronounced both as “reed” (present tense) and “red” (past tense) — but it isn’t spelled like either of those words — and why there are three different spellings for the same sound that is in “two”, “too”, and “to”. So a student who has followed a meaning-based approach will have tools to not only decode the sounds of unfamiliar words, but to have a sense of meaning — and when they apply contextual clues they will almost always be able to recognize words without letter-by-letter decoding.

As someone that has read all of David Kilpatrick’s books, watched a presentation from him, been trained in a Dyslexia Intervention program twice, and has taught Dyslexia Intervention for 5 years, I would like to share my insight of the nonsense word topic. Nonsense words are “silly” words that allow students with Dyslexia the opportunity to best measure decoding abilities. The student literally has to use their knowledge of the alphabetic principle to breakthrough the structure or “code” of the word, phoneme by phoneme. They can no longer hide behind memorization or guessing. Using these words help “rewire” the pathways in their brains and increase the phonemic awareness to automaticity, which is the bread and butter to better reading proficiency. Also, the ability to decode nonsense words fluently, improves their ability to decode multisyllabic words. Multisyllabic words are often made up of nonsense words to begin with. I would suggest reading up on David Kilpatrick’s “Equipped for Reading Success” and “LETRS: An Introduction to Language and Literacy” by Deborah Glaser and Louisa C. Moats.

Multisyllabic words are usually made up of morphemes — word parts that have specific meaning. So I think treating those word elements as if they are nonsense words is foregoing a valuable teaching opportunity, as well as making the overall task of reading and building fluency more difficult for the dyslexic learner.

Also, we welcome your participation here and I am glad that you have read a lot of books and worked as a dyslexia interventionist for five years — but I have been involved in this field now for 26 years– so I write from the context of my own experience. And I just don’t see the point of making things harder for a dyslexic or potentially-dyslexic child in the classroom by adding on an artificial task that is known to be particularly difficult for them and that is not necessary to the end goal of reading.